Boston Globe Article

http://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/2017/09/21/the-curious-world-julian-janowitz/8bmMNcrz21cWeirwe124eO/story.html#comments

The curious world of Julian Janowitz

By Ethan Gilsdorf GLOBE CORRESPONDENT SEPTEMBER 22, 2017

SHUTESBURY — From the second-floor bedroom of his house, Julian Janowitz can survey his kingdom. There is a pond, two dams, fields, the remnants of an old sawmill, meadows, and swaths of woods.

“Moose come to the front door. A bear climbs up on the deck,” says Janowitz. “Forty-one years in paradise. It’s really such a sustaining bliss to be here.”

Since the mid-1970s, Janowitz, a psychiatrist by training who helped found the mental health center at UMass-Amherst, has lived here, on 154 acres in rural Shutesbury. He has gradually shaped this landscape, what he calls “the Bower,” by “constructing stuff”: creating sculptures, many on a massive scale, and scattering them like a leprechaun might hide gold in his magical realm.

“The woods are filled with things that I have made and taken great delight in,” he says. “I’ve been working here for all of these years to make it more beautiful.”

But these days, Janowitz, 88, hasn’t been making any art. He spends much of his time in bed, writing poetry, and reflecting on his life.

“I would suspect this is called dying,” he says. Refusing kidney dialysis, he’s facing end-stage renal failure. But the man defies the odds. “They put me in hospice for a while but I didn’t die so they took me off,” he jokes. “I didn’t think I’d live this long.”

Decades ago, the self-taught artist began fashioning three-dimensional works of stained glass, wood, and stone. Today, dozens pop out of the landscape: a giant hoop, a massive pistol on a stone pedestal, a cluster of white glass structures sprouting like Art Deco-inspired mushrooms. Metal bell-like shapes dangle from trees. Two life-size figures dance on a platform by the 22-acre pond and adjacent bog.

His home is also cram-packed with art: human forms, flames, seed pods, alien beings. Many light up from the inside. Their subject matter is “the connection between men and women.” Many, he says, “have to do with intimacy and what we have about us that has made us human.”

Yet Janowitz’s works are virtually unknown to the public. That may soon change, as his declining health has jump started an effort to determine the future of his property.

Taking a slow breath, he describes the Japanese-inspired house and studio he constructed, the miles of trails he cleared, the stone staircase he cut into a side of a hill, the thousand-foot boardwalk he built across his marshland.

The whole property feels like an extension of his heart and mind, and Janowitz has long let the public walk, cross-country ski, and snowshoe across it, read the poems he’s tacked onto trees, peek at his private sculpture garden, rest on a park bench installed in the middle of his bog, even leave a message there inside a mailbox. He feels strongly that it remain a community resource after he’s gone.

“My vision is very grandiose,” he admits. He imagines a community art, poetry, and “harmony” center blooming here. “I would like it to flower.”

For now, the elaborate dreams are just that. The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation already holds development rights, making the majority of the land protected from development. The immediate goal is to provide public access, ideally in perpetuity. Enter the Kestrel Land Trust, the Amherst-based conservation organization that Julian has chosen to donate most of his land to upon his death.

“It’s a fascinating property, in that there’s been a dance between human influence and nature throughout its history,” says Mark Wamsley, Kestrel’s land conservation manager, giving a visitor a tour of the grounds. The sawmill formed the man-made pond, and Julian’s artwork further “raised the bar for what the property could be.” Ecologically important, visually spectacular, culturally interesting, Janowitz’s property, Wamsley says, will be “a crown jewel for Kestrel.” His land trust will likely partner with other groups to maintain it as an art space and “a spiritual respite, a place to recharge.”

Karen Traub heads up one such local organization, Friends of Julian’s Bower. “We are inspired by what’s he’s done and what he’s created, and feel warmly towards him as a friend and help in whatever way we can,” says Traub, “to help carry his vision forward.”

Wamsley describes Julian as “mischievous” and someone who “believes in things viscerally.” He also has “a hard-nosed side to him,” and is known to be a “deal maker.”

But Janowitz’s deal has been controversial, especially for his children David and Tama. Kestrel will receive 146 acres, the artwork installed on that land, and some of the indoor artworks (which Kestrel land trust could auction to raise money to maintain the property). Julian’s heirs will inherit the house, eight acres of immediately surrounding land, some of the outdoor art, and their pick of the indoor works.

“Kestrel, locals and others are aware I’m not happy with the situation. It’s not what was promised,” says David Janowitz, 59, a retired obstetrician and gynecologist, via telephone from his home in Houston. David, who helped his father build the post-and-beam house when he was a youth, is concerned about litter, noise, and trail maintenance once the property changes ownership and becomes better known.

The other Janowitz offspring is writer Tama Janowitz, 60, best known for the 1986 short story collection, “Slaves of New York.” Her 2016 memoir, “Scream: A Memoir of Glamour and Dysfunction,” opens with a scene of her father telling her, “I have decided to leave you the property.” By chapter two, he’s changed his mind: “So, naturally, Dad disowns me. He decides the give the estate to the Audubon Society instead.”

“My father is a very talented, creative person,” Tama wrote in an e-mail. “It’s unfortunate that, with the present situation, the property is probably not staying in the family.” She worries Kestrel may decide to sell it someday. “But I am glad Dad is pleased.”

Julian Janowitz understands his decision has “stirred up a lot of ambivalence” for his two children. “To give away this kind of thing is a sacrifice on their part,” he says. “But it’s my fantasy and my delight and mine to contribute.”

Meanwhile, David has been traveling up from Texas every couple of months to visit him. Or, as Julian puts it, to “watch me die.”

“Whatever happens,” David adds, “he’s my father.”

Janowitz passes his days facing mortality, in his self-made Shangri-La, on his own terms. “I feel that it’s been a very successful life,” he says. “I’m content.”

“Everything,” he feels, “is right at the very end.”

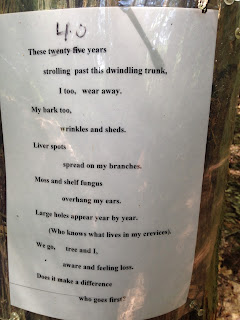

And what is at the end? Janowitz’s fantasy land has clues. One of his laminated poems nailed to a rotting tree stump proclaims, “These twenty five years strolling past this dwindling trunk, I too, wear away.” The words “twenty five” are crossed out, replaced with “40.”

Elsewhere on the property, there’s a structure that looks like two sides of a narrow house, with a red door, and a gong.

The “Magical Doorway.”

“As children walk through the woods they come upon the magical doorway,” Janowitz says. “Well, I always wanted a magical doorway.” So he built one.

It comes with instructions:

This is that very same Magical Doorway in the Woods that you have always read about.

Focus your mind on the goal of overcoming your worst Dark Woods fear.

Gather your resolve, strike the gong, pass through the doorway slowly from this side.

Soon, but hopefully not too soon, Julian Janowitz will also walk through it, for the last time.

Ethan Gilsdorf can be reached at ethan@ethangilsdorf.com

Comments

Post a Comment